What does scholarship mean … really?

Written by Laurie Davies

Reviewed by Briana Houlihan, MBA, G-PM, Dean, College of General Studies

You were born a scientist.

This is what Jacquelyn Kelly, PhD, associate dean of the College of General Studies, used to tell her high school students when she taught scientific inquiry.

Think about it: “When you were baby, you had to learn what actions would get you the things you needed. You tested how to cry to get your parents to meet your needs. We all use patterns to move forward to get what we need,” she’d tell the class. “You’ve been doing this your whole life.”

Well, a few years have elapsed between your first cry and your first research paper. There‚Äôs a difference between conducting scholarly research, and testing an idea, and simply polling your followers on social media. It‚Äôs important to know what each type of testing can and can‚Äôt do for you. Here‚Äôs an overview.Ã˝

The question at hand: What does scholarship mean?

First, let’s distinguish basic inquiry from peer-reviewed, scholarly research by asking a simple question: What does scholarship mean?

And before you roll your eyes, thinking, I’m just over here trying to pass statistics, so how could scholarly research possibly apply to me, know this: Understanding the different types of research and how each can help you is an asset that can and will come in handy during your college and professional career. From course assignments and job interviews to drafting smart, well-cited, on-the-job reports, being able to answer “what does scholarship mean?” may just be the skill that sets you apart from your peers.

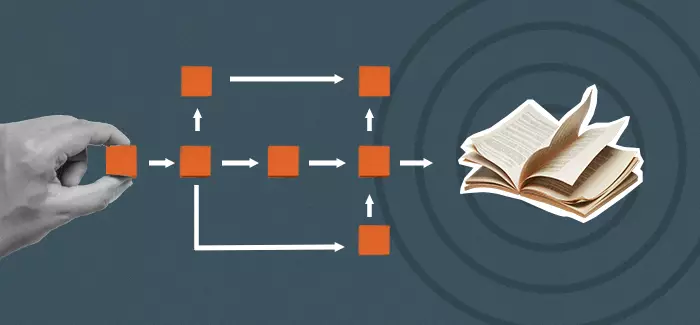

Generally, scholarship or scholarly research follows this systematic process:

1.Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝ Literature review (background on previous research into the topic)

2.Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝ Methodology (how the researchers conducted their study)

3.Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝ Results (what they found)

4.Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝ Data (quantifiable findings that support the authors‚Äô conclusions)

5.Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝ Discussion (what the authors think their findings mean)

6.Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝ Conclusion (recommendation)

For findings to be published, they must be peer-reviewed, meaning they have been vetted (reviewed) by other experts (peers) in the field. And the topics are as diverse as the researchers. Kelly, for instance, has been published recently on topics ranging from to enhancing learning through virtual field experiences .

In other words, it’s not necessarily the what that matters so much as the how when it comes to answering “what does scholarship mean?”

“Scholarly research is generally written for other scholars, but don’t let that deter you from mining [it] and citing it,” Kelly says. “The abstract and conclusion sections may lend solid information to your project.”

We’ll unpack this type of research in a minute, but for now, it’s important to understand that peer-reviewed scholarly research that is published in a scholarly journal is the gold standard for research.

Of course, not everyone (in fact, almost no one) has time to design a research question, conduct a thorough review of literature and design survey methodology. Sometimes you’ve just got to sniff around, survey your peers, throw spaghetti on the wall and see what sticks.

“Any kind of inquiry is important. You’re acquiring information to make decisions,” Kelly says.

It’s just that not all inquiry is created equal. Here’s a basic rundown of different types of research and how they might apply to your project — or your life.

Surface-level inquiry

“I did some research on this, and ….”

You hear this in work settings all the time. Yet, what comes after the word “and” really matters. Actually, what comes before the word “research” matters more.

Was it informal research? Did you just ask a few friends on Facebook? Did you base conclusions only on the clients who receive, open and engage with your email content?

Or was it scholarly research that was peer-reviewed and published in a journal? While most of us won’t be checking that box any time soon, it’s important to understand that informal research or basic inquiry is a fairly low level of “research.” Examples might be:

- Looking a topic up online

- Conducting an unscientific, informal poll

- Asking other people how they’re handling a situation and comparing your actions (researchers call this benchmarking)

Ã˝

Pilots and testing

This kind of testing will be superior to surface-level research. It’s also risky because one successful result from a pilot might lead to a huge investment in a product. (As in a TV pilot that gets canceled after one season.)

You might be testing a message (like an “a” or “b” message in a marketing piece) to see which one has more impact. Or you might be trying to shore up an inefficiency in your company by soliciting feedback from stakeholders and making rapid adjustments. This approach is the way most businesses operate, Kelly says.

Ã˝

And now we’re back to: What does scholarship mean?

The previous type of research — pilots and testing — can yield useful results. “But it’s still like throwing spaghetti on the wall,” Kelly says. “Theory would help hit it out of the park.”

Scholarship doesn’t have this shortcoming. It relies on theory. It is deeply grounded in full reviews of the literature that came before, and it aims to add to an existing body of knowledge. This is essentially the answer to, “What does scholarship mean?”

Not all scholarly research is published. In fact, Kelly and her colleagues in the College of General Studies engage in scholarly research all the time when adapting courses for student benefit.

“We developed a philosophical framework to guide every decision we made in our STEM courses,” Kelly says. “We know why things are working. And if things don’t work the way we expected, we know why and what adjustments to make.”

If you have no plans to conduct scholarly research during your academic career, you may still find it helpful to cite it, especially as you move through university coursework. “Look in the results section to see what kind of answer the researchers found to their question. Dig into the discussion section for context on what it means. Scour the bibliography to find other studies that might be even more relevant to your topic,” Kelly says.

In the end, any inquiry is positive. Curiosity is a good thing. Our world could probably use a little bit more of it. “I want our students asking questions. I want them testing things,” Kelly says.

Whether you’re conducting research or citing it, it’s just important to go in eyes wide open — and know that not all “research” is created equal.

Ã˝

Learn more about General Education at ∆þ…´ ”∆µ, including courses like Psychology of Learning and Critical Thinking in Everyday Life.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

A journalist-turned-marketer, Laurie Davies has been writing since her high school advanced composition teacher told her she broke too many rules. She has worked with ∆þ…´ ”∆µ since 2017, and currently splits her time between blogging and serving as lead writer on the University‚Äôs Academic Annual Report. Previously, she has written marketing content for MADD, Kaiser Permanente, Massage Envy, UPS, and other national brands. She lives in the Phoenix area with her husband and son, who is the best story she‚Äôs ever written.Ã˝

ABOUT THE REVIEWER

Briana Houlihan is the dean of the College of General Studies at ∆þ…´ ”∆µ. For more than 20 years, Houlihan has strongly advocated for first-generation and underserved working learners. She has made it her mission to enhance the skills focus within general education coursework to bring value to undergraduate students from day one of their program.

This article has been vetted by ∆þ…´ ”∆µ's editorial advisory committee.Ã˝

Read more about our editorial process.

Read more articles like this: